The Polymarket effect: When sentiment outruns the spreadsheet

A headline that seems important on Monday morning can feel irrelevant by Monday afternoon. These increasingly compressed cycles actively influence the timing, direction, and intensity of trading responses.

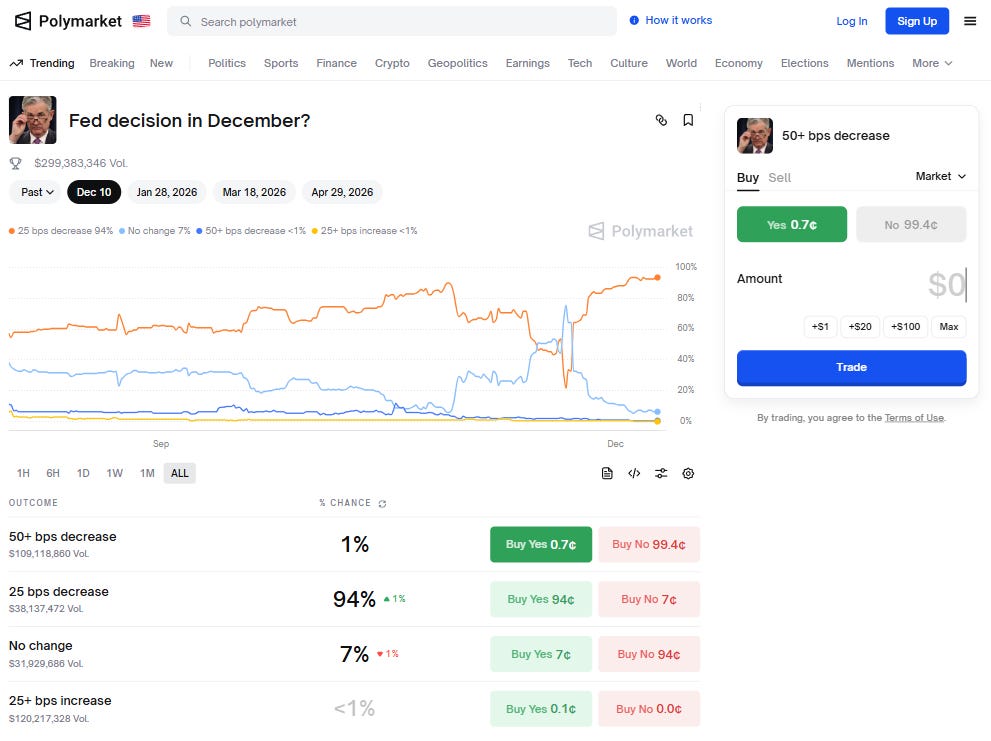

And now we have prediction markets adding fuel to the fire. Prediction markets allow anyone to “put their money where their mouth is”, betting on outcomes ranging from elections and sporting results to how many tweets Elon Musk will fire off in a given week. The breadth of liquidity is significant: more than US$3.6 billion was wagered on the 2024 US election alone, and over US$200 million is currently riding on the next Fed rate decision. And with ICE (owner of the New York Stock Exchange) recently acquiring a stake in Polymarket, these markets are beginning to converge with Wall Street’s own information ecosystem.

What does this mean for markets, and does it risk shaping trading behaviour in a more biased direction?

If prediction markets and fast-moving probabilistic signals become a default reference point, retail investors may be less likely to engage in real fundamental analysis. It’s simply too time-consuming. Instead, many will lean on these market-implied outcomes as shortcuts for decision-making. The result is a widening gap between how institutions trade, grounded in more traditional fundamental analysis, and how retail trades, driven more by momentum and sentiment signals. Over time, this dynamic could amplify feedback loops and mispricing’s as prediction-market consensus begins to substitute for true diligence.

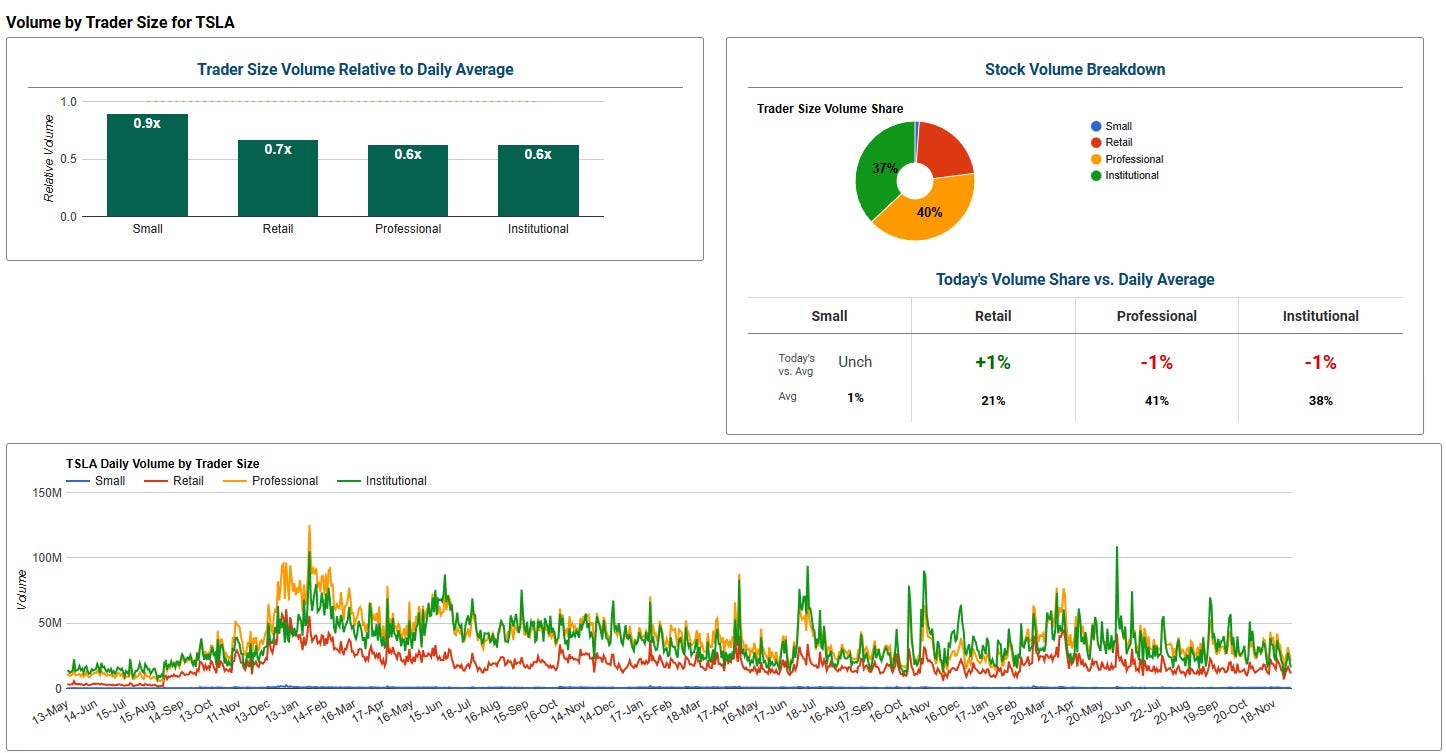

The National Bureau of Economic Research has shown how retail attention shapes market reactions, particularly around surprises. In a study on contrarian behaviour and momentum, it found that retail investors frequently trade against large earnings shocks, buying the dip after bad news or trimming after good news. This behaviour can feed into post-earnings-announcement drift (PEAD), where prices adjust slowly rather than instantly, as theory would predict.

Take a retail-heavy stock like Tesla. When it misses earnings and its fundamental value weakens, retail investors often step in to “buy the dip,” keeping the price temporarily inflated above where institutions see fair value. Institutional holders continue selling, but instead of a sharp repricing, the stock grinds lower over time. The result is a slow, sentiment-driven drift – an inefficiency created not by information gaps, but by the differing behaviours of retail and institutional investors.

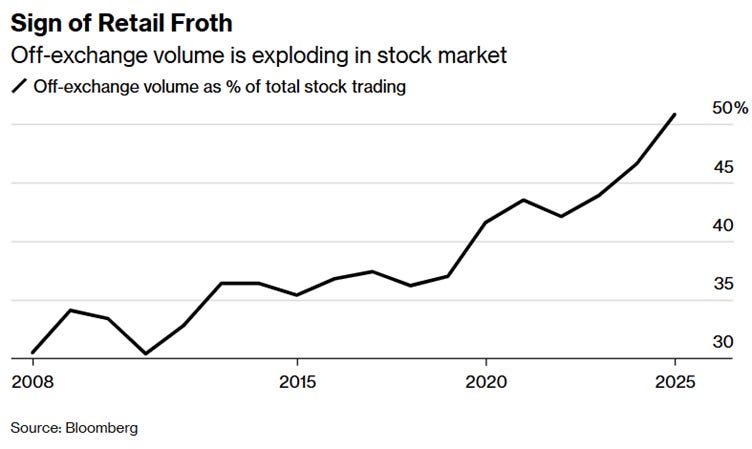

This is significant when you consider the volume of retail participation. The chart above shows that the share of off-exchange trades has risen to 50%, a proxy for retail involvement.

Retail investors love hopping into “the next big thing,”, so markets are being shaped less by spreadsheets and more by stories. The result is a market where prices can deviate from fair value for longer, and corrections unfold over time rather than clean, immediate repricing.

In this environment, understanding the narratives that drive behaviour has become just as critical as understanding the numbers behind the trade.