Why the 8 hour day doesn't work for "knowledge workers"

Plus: the shifting sands of luxury -- the sweet smell of perfume

The other day a young fellow asked me what my hours and my day look like. He was full of pep and enthusiasm — but I admit, the question baffled me. The idea of hours and a set format for a day is foreign to me. I don’t sit at a desk from 9-5 and magically come up with analysis, opinion and investment ideas. The “work” of someone interested in this game we play — stocks — is an ongoing pursuit and it never ends. I am writing this late at night with a spot of insomnia, for instance. In the morning, at 6am, I will likely start to read the FT. At some point I will be at my desk, though I think there is a popular misconception between “being at a desk” and “work” which has led to many office workers believing that sitting their ass at a desk constitutes as “work”. This is not very often the case, unless you are in an entry level position. “Work” happens in the head, then (for me) on the page, on the phone, and in discussion with clients and friends in the field. 9-5, or the concept of any kind of regular day, might as well be a foreign language.

Some preliminaries. The eight hour day has its roots in the labour movements that emerged from the Industrial Revolution. The Industrial Revolution, funnily enough, focused on industry. Most workers employed were partaking in manual labour, which required said eight hours on whatever they were engaged in — spinning cotton or weaving fabric or screwing on toothpaste caps or whatever. The labour part of the equation was inextricably linked with the good produced (and the surplus of labour + material, which went to the owner(s). We are not in the Industrial Age anymore. White collar workers, in my observation, tend to spend a lot of time having meetings (why?), having meetings about meetings (why?) and reviewing what was said in meetings.

Here’s The Atlantic with a good piece about that.

“I think we’ve hit the high point of max human inefficiency in white-collar work,” Jared Spataro, a vice president at Microsoft who focuses on artificial intelligence and work trends, told me. “It sometimes seems as if the modern worker spends more time talking about work than actually working.”

It makes sense why this has happened. We tried to transfer the old ways (8 hour day, chained to a desk/machine/production line) to what is now, for the bulk of white collar workers, “knowledge work”. I have had the misfortune in sitting in some meetings and conferences where I’ve wondered what actual “knowledge” people have. We work in “knowledge” but how much time is spent gaining, refining, and working on that knowledge? After all — that — and the power to contextualise that — is what separates us from the ever-powerful AI. Sitting at a desk has nothing to do with this.

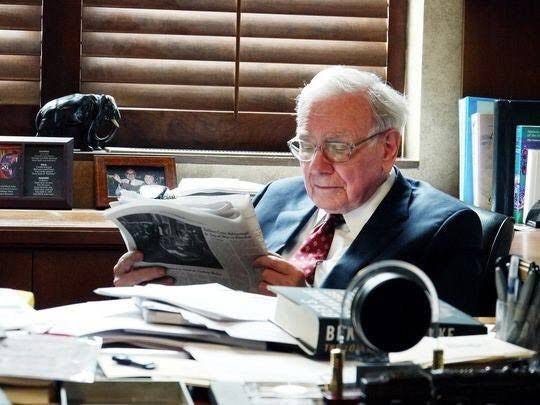

Let’s talk about how I work, because I can only speak for myself. I read a number of papers each day. I read a number of newsletters. I read Twitter, I read some columnists, I read my emails, I read my texts. I spend time understanding the information. There is no point reading and not understanding. I do this every day because if you miss a day in the market it is like missing piano practice, and eventually the audience notices (the great violinist Heifetz used to say “if I miss practice for one day, I notice; two days, the critics notice; three days, the audience notices”).

Then, and only then, do I begin to think about what I write to you here. In between I make emails, make calls, work on things that have a slower burn — my attention is on the Rakon ASM at the moment. I write. I look over what we manage for our high net worths. I discuss ideas. I look at data. All this takes time, reading, thinking.

Something interesting may happen at 9pm that requires attention. I had an email back from a board today later in the evening that required attention. And so on. Nobody will tell you this, but if you are interested in doing “investing” or “finance” in a serious capacity, you are going to work far more than 40 hours, you are going to work weird hours, you are going to work in the weekend; you are going to become addicted to the market because the market is a reflection of humanity. It’s beautiful and ugly and wonderful and endlessly fascinating.

I talk on the phone. You must talk on the phone. I know many Zoomers have a fear of the phone. Phones are great. They are your friend. I probably spend two hours on the phone talking to various people. This is important, because you learn and exchange information and opinion you wouldn’t have otherwise. You can’t live in a bubble.

You don’t do this for a cushy eight hour a day job. Frankly, a company can change in a second (there could be a takeover offer, a change of CEO, a product recall..). You do this because you love the game. That’s the truth of the matter.

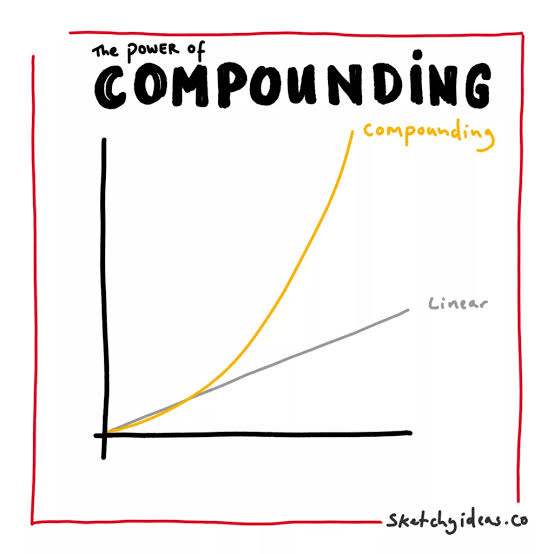

There is also the matter of compounding. You compound knowledge. I know weird autistic facts about companies because I have followed them for a very long time, and it has slowly accrued in my head. If you are young you may not have this (I didn’t), so you will find yourself reading even more. You’re only going to do this if you are passionate. I always think people who are in “finance” for a pay check would be better off being a plumber or something. There’s easier ways to earn a dime. The freaks who rise to the top do so because they are crazy passionate about the subject.

Once I was told a story about the great lawyer Julian Miles, who I later had lunch with over a pork chop and glass of red at Hugo’s. Julian had been given some horribly difficult case (from memory it was one of the cross-claim treaty settlement cases — but I could be wrong — Julian’s CV and list of cases is astounding). He listened to the KC who was handling it, then he poured himself a glass of Chablis, and read over the papers, and within two hours he had written a draft of a submission.

Of course a junior lawyer could not have done this. But Julian had decades of knowledge accumulated — case law, experience, statute, etc. Like they say in the cooking shows — “it’s easy when you know how”.

I am 32. I have been interested in this for a long time. I bought my first book on investing (The Warren Buffett Way) when I was 12 at the Caroline Bay Carnival. I have probably been taking in seriously since I was 24. I have slowly accumulated knowledge. I freely acknowledge I am an idiot. I still have so much more knowledge to compound. “I have promises to keep, and miles to go before I sleep…”

There is no 9-5, there is no eight hours. There is no quick solution. There’s no punching a clock and sitting your ass at a desk and expecting things to magically work for you.

There is building relationships with clients (real, long-lived ones — “your network is your net worth”). There is compounding knowledge. There is making a difference at listed companies (if you choose to do what I do — only for the foolhardy). There is a life-long journey of investing. It is beautiful.

I don’t think endless meetings work. I don’t think proving your worth by working long, pointless, gruelling hours while accomplishing nothing works. I think this model is outdated. I often wonder who this model empowers the most — I think it’s middle-manager bureaucrat (like the ones at so many government ministries, not to mention Auckland Council). They'd have little value without an endless stream of meetings, and nonsense spawned out of said meetings.

At the end of the day, you are going to work 83,200 hours over your life minimum if you worked an eight hour job. You have to ask yourself: would you rather they have a point, or are you happy to fritter them away? I say make it count.

Knowledge work, I think, is a privilege. My real upbringing was in hospo (I am proud of that — which teaches you so much). You work every hour there. There’s no sitting. If you have the privilege of what this is — investing, writing, or markets — then make it count.

World

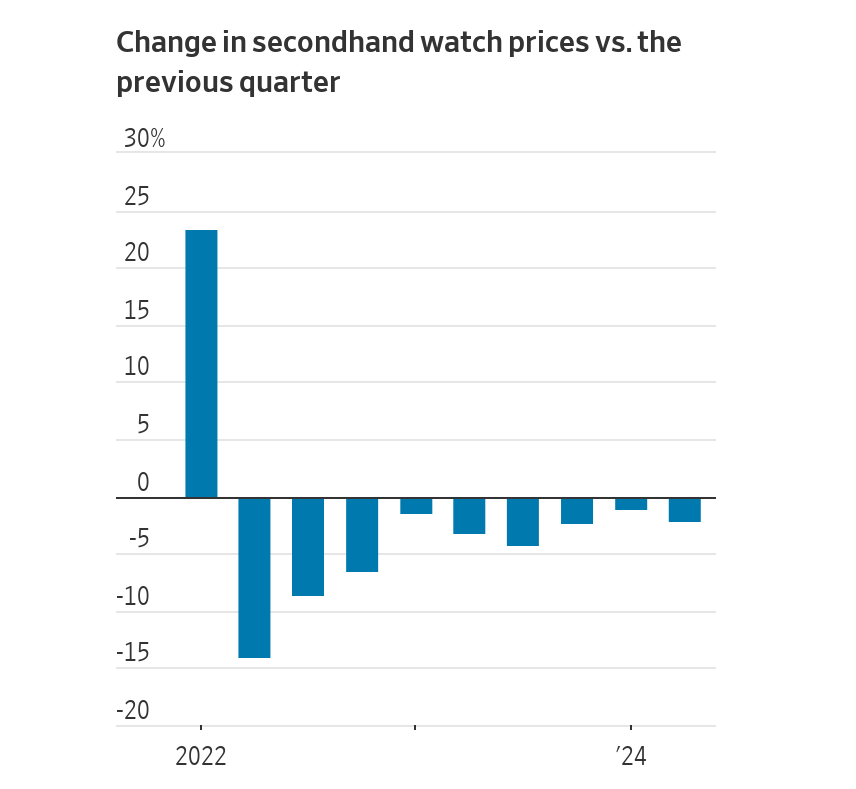

Secondhand watch prices — going down (per the WSJ)

Watches are an “investment” in the same way that art is an “investment”. They’re nice objects of desire but are only worth what the other party is willing to pay. We’ve had an unprecedented bull run in watches, which was a natural flow-on effect from a bull run in the market. Wealth was made and needed to be spent — watches were one beneficiary.

The tide may be turning. On a two year basis, WatchCharts.com’s index is down in excess of 20%.

Meanwhile, sales of watches as reported at the big houses (Richemont, LVMH, etc) are uniformly down. Hard luxury is up — i.e. jewellery — but the tick-tock-clock market is down. I wonder, sort of, if that’s pointing to a vibe shift within the market? Items of luxury consumption decreasing in value seems par for the course when you talk about a recession (in general, luxury good are selling less, but the watch market is particularly sensitive to it, it seems).

But…perfume… is a bright spot

An opposite thing seems to be happening with the perfume sector. Is it the new “lipstick effect” (recession — beauty sales go up). See the relevant chart from the FT below.

What’s in the air? Again — I think this is a subtle shift in the “vibe” — fragrances are mysterious and seductive, they are ineffable. A good fragrance still costs money to produce, too — there’s no shortcuts.

A couple of ways one could play this. You could always buy the direct makers of the perfume (Kering, who owns Creed, Puig, who own Byredo). I already like Kering (it trades well under its median P/E of 20x, has a lot of strong fashion houses and real estate, and is oversold because of Gucci). But a better way to play, I think, would be to own one of the fragrance and flavours makers. There are three majors and one small one I am attached too — Symrise, Givaudan, and IFF. The fourth, much smaller company is Robertet.

The first three make all sorts of flavours and fragrances. They make soda flavours, dish soap scents — you name it, there’s a fragrance (and it's patented). Robertet is a little bit more special, because they specialise in natural raw materials (i.e. not synthesised). It was founded in 1850, and is controlled by the Maubert Family (37%). As you know, I have a preference for family and founder-led companies as they tend to outperform over the long term (the reason being is simple — they have skin in the game). There is a more detailed write-up on Robertet over at French Hidden Champions. Short answer — the family has a multi-generational view which means they can deploy capital over decades with little concern for the market. Add to that the fact that the company deals in raw materials — there is finite land-space and processing know-how for that particularly thing (hence why similar groups have been sold for upwards of 20x EBITDA).

It’s also worth talking about Givaudan (they make components of Chanel No.5). It’s performed well, though not nearly as well as Robertet on a ten year basis. Giuvadan’s history dates back 250 years and they take a similarly long-term view. Consider the fact that flavours and fragrances is a concentrated business, with three major and several minor players — it may be time to consider adding some scent to your portfolio.

A question — guess who one is of Givaudan’s major shareholders is? It isn’t Buffett…