Noise and Simplicity: notes on Chase Coleman, Gates and Buffett

Obsessive Simplicity

Two main takeaways from Carrie Sun’s recent memoir Private Equity, about her time working for Chase Coleman. The first is the importance of systems. No matter how smart you are, if you don’t have systems in place you are going to encounter difficulties. In Sun’s telling, it wasn’t so much that Coleman possessed any particular genius; it’s that he had a system of quantifying information and removing any distracting elements from his life. This is, I guess, one of the best things about being a billionaire — you can remove those elements quite easily. That’s the second element of that first point about systems — simplify, simplify, simplify. Why do I get most of my work done at night, away from the office? Because there’s no distraction — I have simplified every other factor out of it. Frankly, most factors in an office are distracting — idle coffee chat, unimportant questions, and pointless office politics. None of these add anything to anyone’s life and are likely engaged in by people who have little to contribute. Coleman sought to achieve an office where the pointless was avoided, and the Tiger Global machine has done very well because of that.

Another example — Buffett — why is he so successful? Consistency. He gets up every morning, drinks a Coca-Cola, he drives to the McDonald’s, he orders something very unhealthy, and then he goes to the office and reads mostly — he makes a few phone calls with managers of Berkshire’s various companies but mostly he reads — no Bloomberg terminal, no computer. Consistency.

One final example — Steve Jobs. Jobs wore the same thing every day (an Issey Miyake black turtleneck and jeans) to remove that decision from his life. He focused obsessively on simplicity. He was consistent and removed pointless noise.

I spent a long time thinking about this after being in Paris. I had more or less the same routine every day — coffee at the same brassiere, reading the papers — the FT, WSJ, The Times, AFR, etc — and several newsletters I get. Thinking. Reading. Eventually writing. Responding to emails. The bulk of my time was spent reading, though. I was effective — because I was consistent and eliminated every noise factor possible. A man asked me how I could cover so much recently and I at first felt confused — I mean, if you read about LVMH every year you are going to have a pretty good knowledge of it. Knowledge compounds.

The second, almost paradoxical thing I learned from Private Equity was the importance of humanity. That’s why Carrie Sun quit — in spite of Balenciaga handbags and $5,000 spa vouchers and $2,500 Soul Cycle vouchers and a “really, really” nice boss (Coleman) she found herself subsumed by him — her humanity became erased at the expense of Tiger Global and Coleman.

I mean, I’m coming at it both as someone who thinks about investing in companies a lot (how do I maintain my consistency and systems without sacrificing my humanity?) and also from thinking about how employees might feel. A short story. I worked for a mediocre hotel when I was young. It was actually fun — I learnt a lot about humanity. When people are at hotels they let their guards down, you see humanity as it actually is. Everyone in finance should at some point be forced to do a ‘real’ job like this and see the real world. Too often we forget that the equities we own are linked to real people.

Anyway, a very hard working colleague wanted a raise. It wasn’t much. It was probably below what minimum wage is now. The boss — a matronly lady with purple hair — said no. The colleague, of course, left. And x amount of time went into training up a new person — who was hopeless by the way. The amount of time that went into training far surpassed the amount that a small raise would’ve cost. Why do employers consistently make this mistake?

Another example — my friend who worked at unnamed Canadian Pension Fund told me that once you’re on that train you’re set for life. MBA? Great. Wharton? Even better. Just sit your ass on your Aeron chair and collect your salary, and get promoted every year (great article from Elevation Capital’s weekly reading — always a must read). This, I believe, is called failing upwards.

My mind has been on these two questions: i) how do I improve my systems? And ii) when I’m investing, how do I know if management is engaged in fallacies as mentioned above? It’s hard to know because often these decisions sit with middle management — you don’t get them on an earnings call; the CEO is likely clueless. The best solution I can think of is what Phil Fisher called scuttlebutt — make friends with “lowly” employees - chat to them. Go into a store, if applicable, watch the traffic, watch how people are treated. Book lunch with upper management and watch how they treat waitstaff. A simple, but often overlooked maxim: GOOD PEOPLE = GOOD MANAGERS.

The flaws in my systems (the flaw is always yourself)

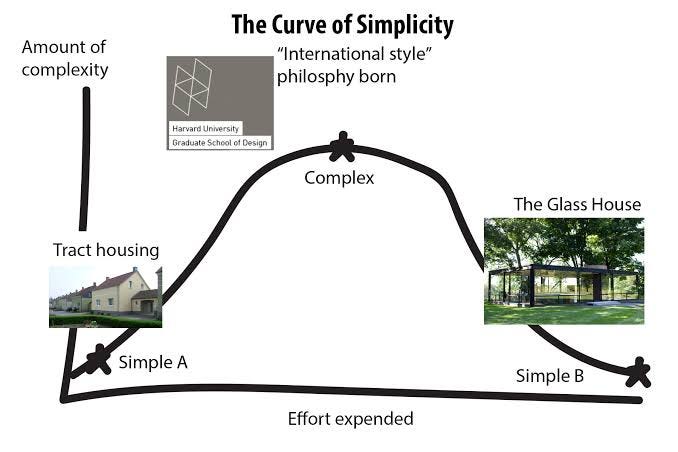

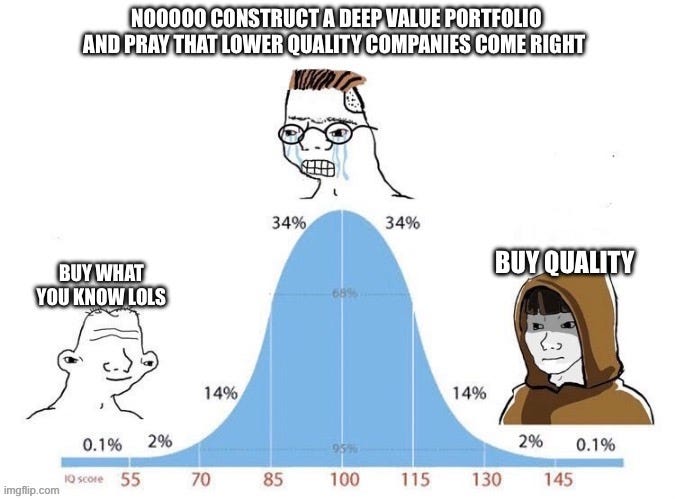

Turning back to i) — where are the flaws in my systems? One is focusing on no-hoper companies hoping for a turnaround. I don’t know what to do about the NZX; I have a set of charts prepared and I am willing to engage with management but I keep thinking — why not just buy Mastercard or Booking Holdings and keep it simple, dummy? (Mastercard has a 53% ROIC, while Booking Holdings has a 36% ROIC). There are logical reasons for focusing on no-hoper companies, or poorly run companies — NZ is a small market and you can have an outsized impact as a result. I couldn’t, say, do the same in the US without billions of dollars at my disposal. Elliot Management has done well out of this system.

Another flaw is emotion — my classic example for this is Doc Martens, a company I did a lot of research on that then did very poorly. I should’ve just said — hey, this is a bad position, let’s move on. Why did I keep on believing in the favourite shoes of now-Green party leader Ms. Swarbrick? Emotion, ego — enemies of good investment (again, a paradox here — emotion is why people buy some many things; why do people buy LVMH products, or why does Porsche have such an emotional impact on some people?)

This is the investing paradox — you often want companies that provoke emotion, but you want to keep your own emotion out of it (but but but — my initial fascination with Brunello was provoked by a years-old NY’r article then by my partner’s massive pile of Brunello scarves. There’s no hard-and-fast-rule — damn).

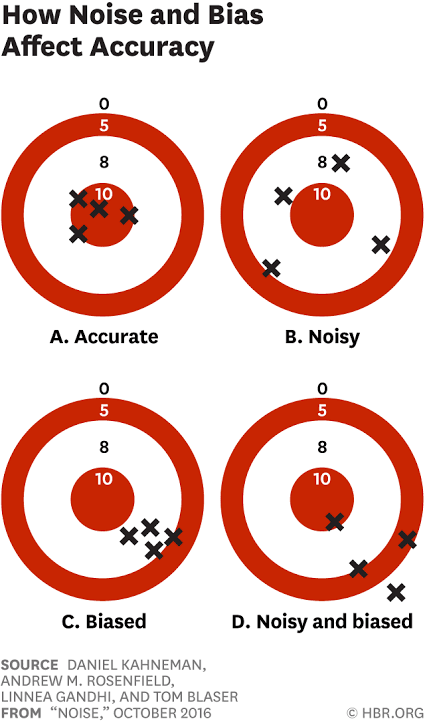

The second way I’m improving how I think about investing is by reducing external noise to as little as possible. My job is to make opinion and analysis of companies, and to advise our clients who have signed up to be advised by me. Everything else is secondary to this, and often pointless. The way I am personally improving my process is my eliminating the pointless.

Bringing it all back home

Anyway — should we talk about numbers? Here’s a glance of our investable universe —

There are several studies which show that ROIC and top line growth are the main factors in the success of an investment12 (10 yr rev CAGR is the one scrawled to the far right - ‘23, then ‘24 ROIC is on the left). If you actually run the numbers McDonald’s consistently achieves a consistent ROIC, but its 10 yr CAGR is flat. MSCI, on the other hand — holy guacamole — +30% ROIC and double digit revenue growth over the last ten years (as Munger is fond of pointing out, it doesn’t matter what you pay if you achieve a good ROIC over time — you’re going to end up with a helluva result). That’s one way I’m looking at maintaining systems. I’ve articulated it in a very scientific meme below:

Certain companies don’t work with this screen (Bollere, Exor, etc). NAV is sometimes a more appropriate measure. And here I’m going to admit my bias — even though MSFT screens really well I’m loathe to buy something that looks “toppy” — they also saw a fall in ROIC as they invested heavily into AI3. On the other hand, Starbucks looks like a no-brainer — it achieves almost double digit top-line growth, it has +27% ROIC, and has a barrier to entry (it’s Starbucks). It’s also sat around that $90 range since 2020 — a lot of reasons why (Covid, staff strikes, and now boycotts related to Israel). I didn’t highlight WMG or UMG but they both look good as well. On the other hand, Madison Square Garden Sports feels like a good investment (it is an irreplaceable asset — you get to own the Knicks, and the Rangers, and an Ice Hockey team, etc) but it suffers from Jimmy Dolan’s “discount” (he’s not a good manager, and an infamous try-hard who bans people from Madison Square Garden by blacklisting his enemies).

What about scuttlebutt? Or: why Bill Gates won the 90s

The other thing — how do you make sure the managers at the companies you’re invested in aren’t run by terrible managers who either skimp on the “little people” or let people fail upwards? One technique Bill Gates used to employ — actually, let me just quote it in full. It’s fun, I promise — I’m sanitising it a little to make it PG4

Bill came in.

I thought about how strange it was that he had two legs, two arms, one head, etc., almost exactly like a regular human being.

He had my spec in his hand.

He had my spec in his hand!

He sat down and exchanged witty banter with an executive I did not know that made no sense to me. A few people laughed.

Bill turned to me.

I noticed that there were comments in the margins of my spec. He had read the first page!

He had read the first page of my spec and written little notes in the margin!

Considering that we only got him the spec about 24 hours earlier, he must have read it the night before.

He was asking questions. I was answering them. They were pretty easy, but I can’t for the life of me remember what they were, because I couldn’t stop noticing that he was flipping through the spec…

He was flipping through the spec! [Calm down, what are you a little girl?]

… and THERE WERE NOTES IN ALL THE MARGINS. ON EVERY PAGE OF THE SPEC. HE HAD READ THE WHOLE GODDAMNED THING AND WRITTEN NOTES IN THE MARGINS.

He Read The Whole Thing! [OMG SQUEEE!]

The questions got harder and more detailed.

They seemed a little bit random. By now I was used to thinking of Bill as my buddy. He’s a nice guy! He read my spec! He probably just wants to ask me a few questions about the comments in the margins! I’ll open a bug in the bug tracker for each of his comments and makes sure it gets addressed, pronto!

Finally the killer question.

“I don’t know, you guys,” Bill said, “Is anyone really looking into all the details of how to do this? Like, all those date and time functions. Excel has so many date and time functions. Is Basic going to have the same functions? Will they all work the same way?”

“Yes,” I said, “except for January and February, 1900.”

Silence.

Yeah, that’s why Bill Gates dominated the 90s — that’s why Microsoft had the upper hand. The dude was reading spec sheets from bottom to top and he knew it all. I guess, I don’t know, you could’ve looked into this “Microsoft” company in the 90s and talked to the employees and you probably could've ascertained nobody was going to be failing upwards there. Nowadays Microsoft has about twenty or thirty layers between management — as does Google (Alphabet) and all the other tech giants. I suspect they have got fat and lazy. Alex Komoroske makes the case well here — Why Organisations are like Slime Molds — must read. Link. Komoroske is the current head of corporate strategy at Stripe. Avoiding those organisational layers — managers upon managers — is a never-ending battle. Komoroske is more or less making the case for more simplicity — i.e. what Chase Coleman, Buffett, and Jobs all look for.

Nipping bad culture in the bud

Why does Hermès work? It’s not just because they have the Birkin. It’s because their structure is completely decentralised — they trust the perfume department to do their thing, they trust the clothing department to do their thing, and so on. They avoid what I’ve started to term tattle-tale culture. Think about the power of reciprocity (I do something for you, you do something for me). It’s almost perverted in this instance — “I tattle-tale on you, the boss owes me x”. This is a horrible way of conducting oneself. Hermes does it by decentralising. Mainfreight does it by incentivising. Bill Gates did it by asking for total understanding of your job. Different ways, same result.

One final thing to think about — a friend of mine worked at Bvalgari. The tattle tale culture was rife. Employees were ripping into one another. LVMH promptly replaced the manager and sent in their best trouble-shooter in the Southern Hemisphere. They nipped it in the bud.

https://hbr.org/1986/01/do-your-business-units-create-shareholder-value

https://www.morganstanley.com/im/publication/insights/articles/article_returnoninvestedcapital.pdf

I have played with Chat GPT and I have tried to make a GPT that writes like me by feeding it every newsletter I’ve written — it still doesn’t work. Here’s what the custom GPT I made throws up when I say “write about how I haven’t been able to make GPT write like me”:

Despite numerous attempts, I've encountered a peculiar challenge: ChatGPT, this articulate and adaptable AI, seems to stumble when it comes to emulating my distinct writing style. I've thrown various prompts its way, hoping to see my own reflections mirrored back in its responses, yet the outcome often misses the mark. It's a curious situation, akin to teaching a highly skilled mimic the nuances of a rare dialect. Each interaction, rather than closing the gap, somehow emphasizes the subtle complexities and unique cadence that characterizes my prose. This experience has been an intriguing exploration of the boundaries of AI's capabilities to replicate the deeply personal and idiosyncratic nature of individual writing styles.

Like they say — you can’t emulate a knacker from Oamaru!

https://www.joelonsoftware.com/2006/06/16/my-first-billg-review/