Tariffs, but like a supermarket

Why you shouldn't panic

Stimulus in China — We’re still in Trump tariff land, though I still tend to think a lot is bluster — you’ve even got his (ex?) bestie Musk advocating for 0% tariffs in Europe (I mean, a 45% decline in European Tesla sales might have something to do with it…).

Per Bloomberg — expecting more stimmy in China, cutting the BOC rate down to 1.4% and likely to increase stimulus across the board. This is good for luxury goods companies, as much of their merchandise is sold to China — that’s great news, as sales for LVMH’s cohort of houses in China saw a +3% drop in sales YoY. LVMH stock is down +20% year to date.

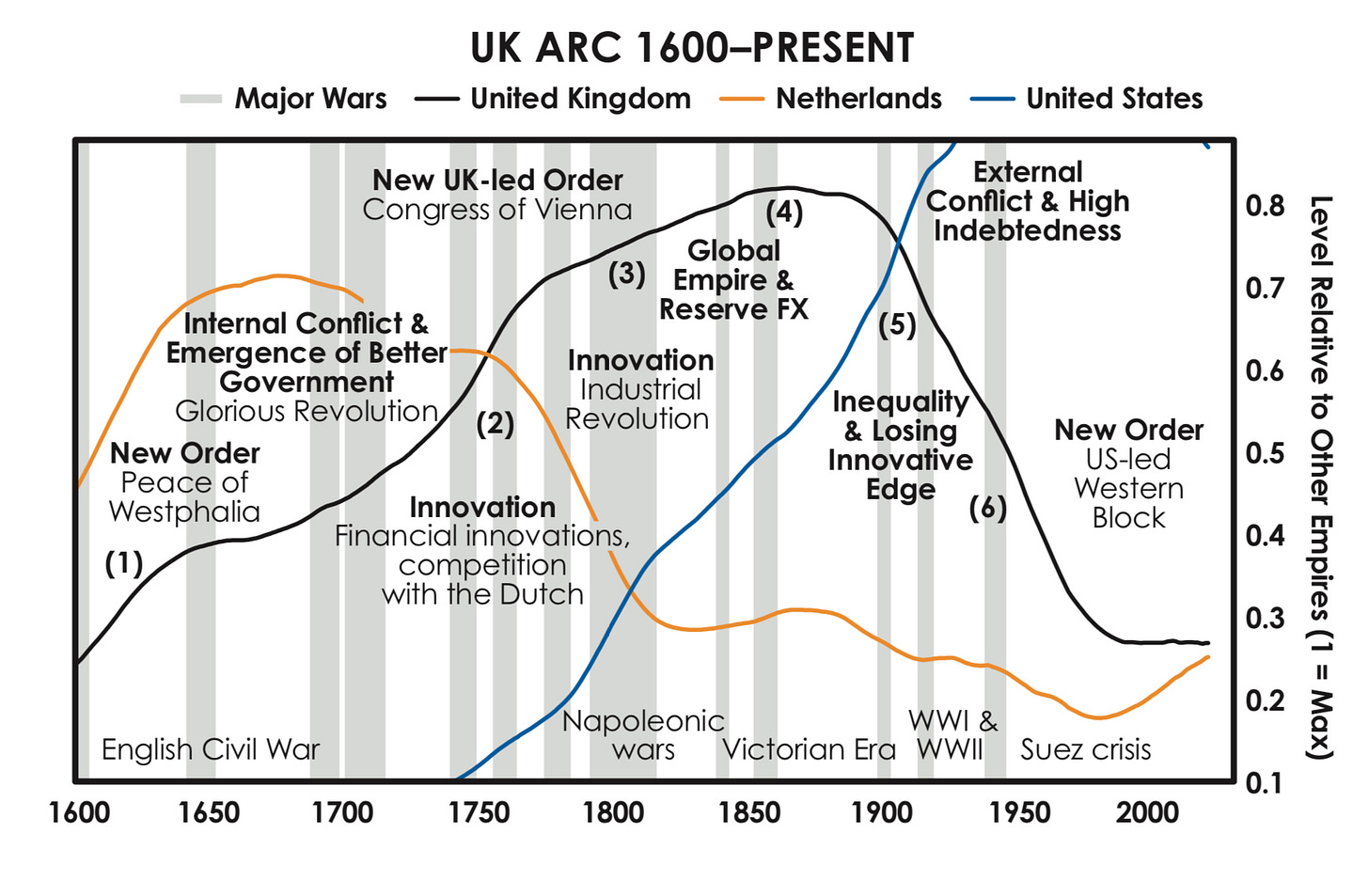

I’ve talked a little bit about Trump and co’s desire to see the end of globalisation — the irony of which is that the US has been the main beneficiary of globalisation. I’ve also talked about the potential for the US dollar to lose its status as reserve currency — if you are the reserve currency you have the biggest swinging d***1 (BSD). The UK was the reserve currency for a while, and it was the biggest player in the world economy — see Ray Dalio’s chart below:

When you are the reserve currency you get to determine your own terms. You are the monopoly banker. If suddenly the preferred reserve currency is say, the Chinese Yuan or the Euro, then they get to be the monopoly banker and the US loses that very desirable power. Nobody wants that. That’s why you’ve got a tranche of bankers and investors — Jamie Dimon, Bill Ackman, Musk, etc — all balking at tariffs. They know what's at stake.

Moving back to China, the opportunity set is fairly clear — if you are a luxury house and you don’t want to deal with tariffs then you sell more to China (and everyone else). Why bother with the US? The rich will just fly to Europe to buy their Birkins there anyway.

If you are the Chinese government and suddenly Trump goes ok, tariffs are going to be, like, 110% it’s the equivalent of a child going “well, I double triple dare you, no take backs!!”. The Chinese government is fairly competent so their response is to introduce stimulus and make it more attractive to do business with China.

I don’t particularly think the tariffs will stick. I think a lot is bluster. I also think the business community of the US, which funds politicians via SuperPACs and so on, are not particularly enamoured with tariffs either. I don’t think the US would like to stop being the reserve currency. I also think, more importantly, that the US contains a collection of world-class businesses that remain world-class.

So here’s what I’m doing: Not Panicking.

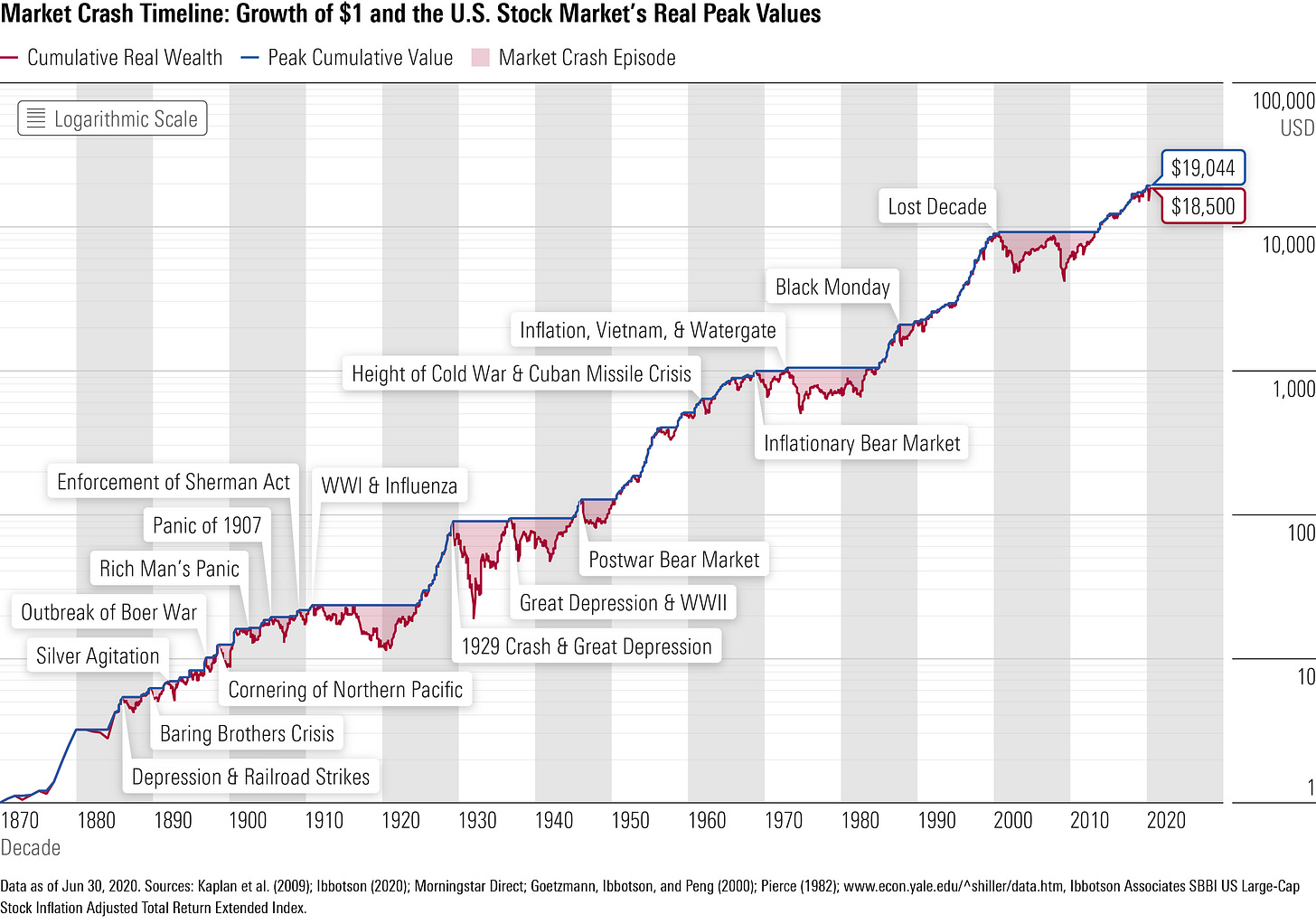

Listen, the US has survived the depression of WWI, the Great Depression, the depression of WWII, oil shocks, the dot com bubble, the GFC, the COVID-sell off. It’ll likely survive this. See below a chart showing the growth since 1871:

In the scope of history, that $1 survived very well indeed. Panicking and running for the hills does not do so well. Winston Churchill was a great and flawed man but a terrible investor; he bought and sold shares prior to the 1929 crash in such speculative investments as mining companies, railways, and so on — most of them lost money (hence why Churchill continued to write at such a pace — to fund his Champagne-and-spec stock lifestyle). Hetty Green, on the other hand, (known as the “Queen of Wall Street”, managed to do very well her time — her quote?

I buy when things are low and no one wants them. I keep them until they go up, and people are crazy to get them.

Now, that’s something I can get behind.

Nobody wanted Meta a few years ago. I wrote an internal memo, close to its plummet in ‘22 (it got to $99 or so a share!). I wrote this:

ii) Yet what if we were to tell about about a company with this set of heuristics? Let’s call it “Company A”

Company A has a 31% return on equity and a 20% return on capital.

It has a net income margin of 37% and a FCF margin of 21%

Its income has a compounded annual growth rate over the last 5 years of 41%

If we add in numbers, now, let’s say the net income for 2020 was $29 billion, and $10 billion of that was used to repurchase stock from shareholders?

Let’s say the unlevered FCF is around $6 billion per quarter, and let’s say the debt to equity ratio is about 9x.

In other words, Company A is grows at a quick clip, and has done sustainably for the majority of its life. Its return on capital and return on equity would make any investor happy. Its FCF is an absolute machine.

Would you buy Company A?

Company A was Meta. You would’ve roughly made 4x or 5x’d your money if you’d bought around then. The point is, the fundamentals of a business matter, and right now there a quite a few exceptional businesses with good fundamentals trading at a good price. Alphabet (Google) trades at ~16x earnings. LVMH trades at ~18x earnings. And so on. Brown-Forman trades at ~15x earnings. These are all “inevitables” — Google will continue to be a dominant advertising platform, LVMH will continue to sell luxury, and Brown-Forman will continue to sell Jack Daniel’s and so on.

I talked to my ma in the weekend. She is not really a share person. Her portfolio is a bunch of “inevitables”. It’s done very well. She said “aren’t you worried about this stock market?”, and I said “You love supermarket shopping, Mum. If you see something at a 25% discount you buy it. You come home, and you’re delighted that you found some mince on special2”

She was like, “oh, that makes sense”.

The problem is you have a lot of people looking at charts and catching worry that the world will end. The world, I am delighted to say, has a magnificent disposition to carry on.

See below for those interested — reproduction of my entire internal memo — The company that ate the world (c. Late 2021)

It may seem bizarre to write an investment thesis on Facebook in 2021. Facebook has a giant market capitalisation and its product suite is well known. 3.5 billion people use its products, or around half of the population of the world. Yet we think Facebook presents an opportunity to own a cash flow generation machine with monopolistic-like characteristics.

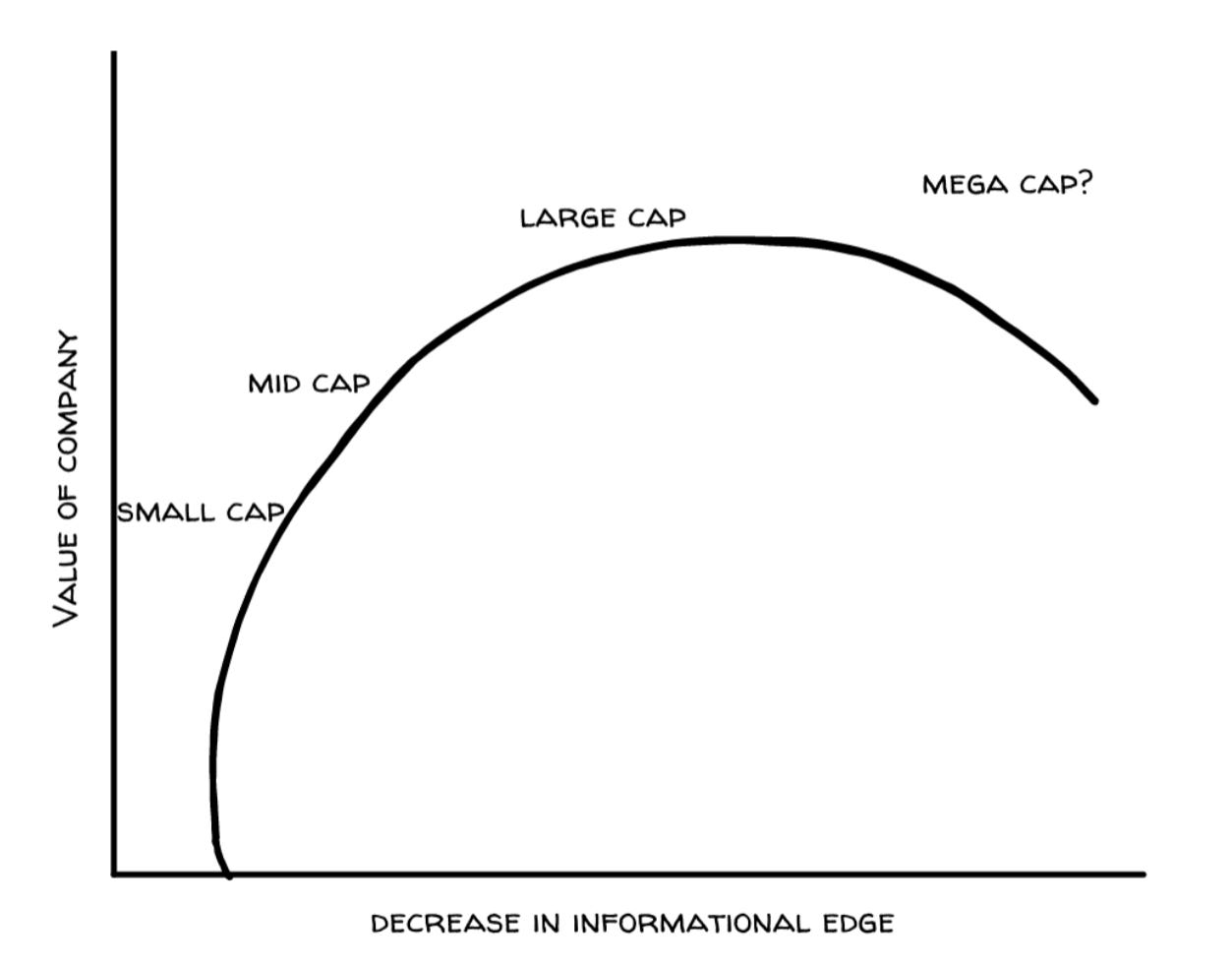

i) The psychology of the whale

There is an unusual phenomenon that we’ve noticed occur with mega caps. They are already in the top percentile of the entire listed market; so how much more upside do they present? We are seduced by fables of “ten baggers” and “hundred baggers”: the reward they present is much greater than an established company. As investors we so often find ourselves crate digging -- the traditional understanding of what gives an investor “edge” is having access to knowledge someone else doesn't. Typically one way of doing this is finding a company which is less covered. The traditional understanding of “edge” is that the more coverage a company has the less likelihood there will be of an edge. More analysts are covering it, more people understand it, and every piece of information about the company is likely parsed and analysed to kingdom come. The implied assumption is that the market tends to be efficient at valuing mega-caps because all of the possible information is understood and the companies in question make up substantial portions of major indexes which are held by countless institutions.

We would like to propose that there is a discrepancy with information-analysis theory. At some point when a company reaches mega-cap status everyone assumes that everyone else has the same amount of information. The information becomes inefficient again. It is akin to everyone assuming the supermarket will be busy on a certain day so they wait til the next day; the next day is busy because everyone assumes the same. This distortion might be expressed like so:

It is if, once a company becomes a mega-cap, the market (and remember, the market is just people) makes a series of assumptions that everyone else must be valuing the company the same. It is a self-fulfilling prophecy.

What we ask is, what if there is a kind of information density block which occurs? Our understanding of the company becomes skewed by the gargantuan size of the company’s market capitalisation.

ii) Yet what if we were to tell about about a company with this set of heuristics? Let’s call it “Company A”

Company A has a 31% return on equity and a 20% return on capital.

It has a net income margin of 37% and a FCF margin of 21%

Its income has a compounded annual growth rate over the last 5 years of 41%

If we add in numbers, now, let’s say the net income for 2020 was $29 billion, and $10 billion of that was used to repurchase stock from shareholders?

Let’s say the unlevered FCF is around $6 billion per quarter, and let’s say the debt to equity ratio is about 9x.

In other words, Company A is grows at a quick clip, and has done sustainably for the majority of its life. Its return on capital and return on equity would make any investor happy. Its FCF is an absolute machine.

Would you buy Company A?

iii)

Company A is, of course, Facebook.

iv) Now consider Facebook’s business. This may seem obvious, but perhaps the entire premise of this investment idea is that humans so often let the obvious pass them by.

Facebook’s namesake platform is a social network which has 2.85 billion active users (around a quarter of the world). The average user spends 35 minutes a day on Facebook, or 99,750,000,000 minutes per day. That is an extraordinary amount of time in front of a screen, or “bums on seats”. Facebook allows users to post and share information, but it also acts as a hub for community pages, small businesses and Facebook Marketplace has fast become a ecommerce giant with upwards of 1 billion users. Facebook’s adjacent platform, Messenger, is integrated tightly in many people’s daily lives and often used as their main form of communication.

Instagram has 1.36 billion users. It attracts a different demographic to Facebook’s audience, which skews slightly older. On average Instagram is used for 28 minutes a day. The time spent using it increases in proportion with the user’s age -- Gen Z typically spends 57 minutes per day on Instagram.

Instagram is a particularly malleable platform; it has its own marketplace (instagram marketplace) and when Snapchat’s “stories” feature proved to be a hit, Instagram simply implemented its own version of “stories” (which Facebook’s namesake soon implemented too). More people use Instagram and Facebook’s “stories” platform now - 1 billion Facebook and Instagram users, in comparison to Snapchat’s 120 million.

WhatsApp is the third platform to Facebook’s holy trinity. It is a cross-purpose messaging app with two billion users. In total, Facebook’s platforms occupy #1, #3, #4 and #5 of the most-used social media platforms worldwide. Facebook has an unprecedented dominance worldwide which is so complete that it almost creates cognitive dissonance.

v) In praise of mega-caps

We want to highlight Warren Buffett’s purchase of Apple in 2019 (he did hold a holding position before this, from 2016); the stock has tripled since then. Apple was already a large company in 2019. It was already a mega cap. Yet price tells us nothing about value, as Buffett’s purchase shows us. It does not matter if the company is worth 100 million or 100 trillion: the market capitalisation tells us nothing about the characteristics of the business.

vi) Ignoring what’s right in front of your face

We have made the same mistake of ignoring what is obvious multiple times. The most obvious is Microsoft, which has since become a mega-cap. Yet (we are humbled to say) the list is long -- Xero and Adobe are another pair of examples. The software of all these companies touch our daily lives inextricably; we use Adobe’s product suite daily. How did we miss it?

Why do people miss the obvious? It seems to be a curious cognitive bias which afflicts humans on a daily basis. Alejandro Lleras puts it this way:

Alejandro Lleras, a professor of psychology who has studied what he calls the science of missing the obvious, found that when the brain has been affected by previous events, it creates biases against certain images it deems distracting. It’s the brain’s way of searching and sorting. For example, if (as in one of his experiments), you’re told to find a picture of a face among flashing images of houses, your brain will create a bias against images of houses so it can spot the face. If you’re next asked to find the picture of a house among flashing images of faces, you’re more likely to miss the house because of the bias that carries over from the previous test.

Is it possible that as investors we are searching for the face amongst the houses? Even if it’s a really good house?

vi) We propose that Facebook is a little like an incredible house in Lieras’ experiment. You can’t see it if you’re not looking. But Facebook is afflicted by a couple of other psychological assumptions, too. The title of this note is The Company that ate the world. Facebook’s user base is so big its value as a company is hiding in plain sight. Roughly half the population of the world uses its products in some way. It’s dominance is so large it is a little like pointing out something very large, like the moon. Of course it’s there, we think.

vii) Is Facebook perhaps good value?

My point

My point is, obviously, is don’t panic. I felt like an idiot calling Meta/Facebook a value stock. My continued writing for why Brown-Forman and associated booze companies, as well as why companies like Alphabet are good value, is a continuation of this. The more the market sells off, the more value is to be found.

“But everyone wanted to be a Big Swinging D***, even the women. Big Swinging D***-ettes.” ― Michael Lewis, Liar's Poker

She only buys on special.