Why most fund managers underperform

Plus -- the continuing melodrama of Rakon

I read with interest Brent Sheather’s recent column in NBR on the endless passive vs. active debate. He notes, rightly, that most fund managers underperform a passive index (there’s a reason most “investment gurus” dogmatically tell you to invest in an index fund — for the large part, they work). He attributes most of the reason for underperformance to fees and skewness (i.e. the best performing 4% of stocks of the S&P 500 are responsible for outperformance of the index as a whole). All very well — but it got me thinking, i) what are the other reasons and ii) do we still have superinvestors?

The more important reason for underperformance is something most fund managers will never tell you. They are beholden to the quarter (or even month!). This is because they earn their living from being a fund manager and they often have retail clients who see a bad quarter and freak out — sometimes they withdraw money. I am always talking about incentives — so think about the incentives here — you a) earn your living from doing this and you b) know your clients will freak if you lose money, even for a quarter. The solution is to have a portfolio which is not so volatile. You, as fund manager, get to keep your job (yay!) and they, the client, get a nice positive return — not matter how small (yay!). Everybody is happy.

The most common way to make a volatility-lite portfolio is to follow the crowd. This is often called “index hugging”. Most fund managers do this. If you take the top holdings of multiple NZ funds you will find they have similar allocations. The same names will litter their portfolios. A cursory look at a number of global NZ funds shows that most own multiple names like Apple, Microsoft, Nvidia, etc — Apple and the rest of the “Magnificent Seven” have driven the performance of the S&P 500. Ergo, owning the top performing names gives you most of those index-related returns. Note below a selection of global-orientated NZ funds with names redacted (n.b. We have been long Alphabet for some time…)

Mag 7 holdings per sample —

Alphabet - 5x; Apple - 5x; Microsoft - 5x; Meta - 3x; Amazon - 3x; NVIDIA - 3x

I don’t have any judgement of fund managers who do this. They need to earn a living. It insulates their portfolios from volatility (most of the time!) and gives clients a positive return. Also — some Mag 7 names offer good value — GOOG trades around 26x earnings; Meta was at one point trading in the low teens.

On the other hand, nobody is going to outperform by skewing entirely towards consensus names — you might as well own a passive index fund (you might say — but what will the fund managers who go on TV and Bloomberg have to say, then?)

Obviously indexes have performed very well in recent memory. It seems those that remember the GFC are a dying breed. The GFC is remembered in movies like “The Big Short” where, ironically, people learn all the quotes but never all the lessons. COVID was propped up by a large amount of QE. Most young people have not seen a big recession. I suspect until we have a large recession most people will continue to “buy the dip” and bolster index funds allocations (more on the problems with this later).

Back to fundies — this is the problem they suffer. Their hands are tied. Most retail investors are stuck on the positive-return hamster wheel, prone to a heart attack if they see a negative return. There has been a lot of Buffett-worship lately — especially in the wake of St. Munger’s death. Yet what if we took a look at Munger’s record, during his early investment partnership days?

Some eye-popping returns — but look at those two -31.00% years! (That’s negative 31.00%). How many of those who profess to worship at the altar of Buffett and co would be able to stomach those? Note the volatility — that’s almost double what the S&P offered. The performance varies wildly — in ‘72 Munger only returned 8.3%, whereas the S&P returned +18.00%. 1970 was barely better — St. Munger barely broke even. How many investors would be happy with this? Moreover — how many investors would running for the hills, cash in hand, giving their money to some shyster with soothing and reassuring rhetoric and single-digit returns?

You can find the same results with many other “super-investors”. Every time they have a down year the press (and their rivals) are there to ask “has x had his day?” Frankly, it is a lot easier to have an industry based passive investing. Money go in, small fee go out, returns go up (so long as nothing bad happens).

It is true if you invest in the S&P 500 and never take any money out you will have historically made back all your losses. See below, with bear markets marked in yellow.

It’s all very nice to think about — though what people don’t always think about is the time it takes to recover. The Dow Jones did not return to its 1929 highs until 25 years later. It also doesn’t take into account the habit of people panic selling — to think that people wouldn’t panic sell should another recession come along is fanciful wishful thinking. People are their own worst enemy.

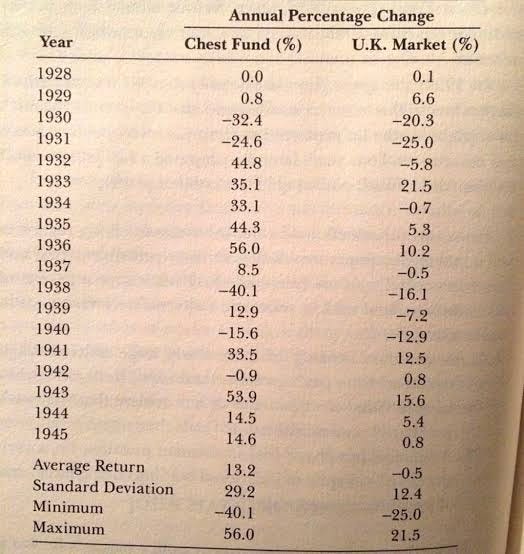

I want to present you with another stellar investment record. It averaged 13.2% versus the 0.5% of the UK market at the time. There were four severe drawdowns. Take a look — and then take a guess at who it is.

It is, of course, the record of Keynes while managing money for Kings College. Keynes is probably the greatest economist of the 20th century. Look at those drawdowns! Can you imagine the headlines today? “40% drawdown at fund…Keynes asunder!”

If you want to get outsized returns you need to be prepared for drawdowns. It will feel horrible. You will question yourself and you will wonder if you are a terrible investor (if you don’t wonder this every day you’re doing it wrong). You will be laughed at. You will have clients pull money out. You will have sleepless nights. The best solution to think is to run money for people who have a sense of permanent capital — they get you, they understand what you’re doing, and they understand your process (I don’t think many of the well-heeled money managers going to Omaha to press the flesh are in this category; I strongly suspect the well-off farmers who invested in Berkshire early on are).

This creates a disadvantage that few want to talk about. The well endowed family trust, foundation, office or otherwise has enough capital to survive harsh periods. From my very few years doing this thing (“managing capital and trying to grow it”) I have noticed the people with the most capital call you the least. You have lunch once every so often, they say cool, great, and off you go — it’s a perfect relationship.

If you are a retail investor, though, and your net worth is under $1mn liquid (I’m pulling this number out of the air), then you are in a different spot entirely. You either need to be willing to give up things or have an iron gut if you want to be afforded the same opportunity as those high net worths we talked about above (“the advantage of sitting on your ass and waiting”). Many do not and are, unfortunately, forced to sell off holdings to fund a house repair, school fees or general keeping-up-with-the-Jones’-related-expenses1 (I suspect those Jones-related expenses consume more than most would like to admit). This is a massive disadvantage — you can’t wait out a drawdown if you’re not liquid and need to pay for a roof or whatever.

I say liquid deliberately. Lots of people — New Zealanders particularly — have equity in their house. It is not cash. It is equity. The difference is distinct. There is a good essay by Seth Klarman called “the painful decision to hold cash” and it outlines quite well why cash is different. You hold it; it generates a negative return (inflation), and you wait in hope of an opportunity. Even if you rotate this money in T-Bills or a term deposit you are still more or less bobbing along the River Styx with a flat return — once you have been taxed on your TD or T-Bill you are merely matching the pace of inflation.

Most of New Zealanders are invested in KiwiSaver options and PIE funds that unfortunately aim to keep up with the indexes rather than outperform them. This is only to be expected. The bulk of so-called financial influencers peddle index funds — the message is: index fund-like returns or else (there’s alternatives: there are a number of like-minded investors in NZ, but their numbers are few).

As always, I like to think about Jacobi and what the inversion might be. The answer seems pretty simple — i) have time on your side and ii) be willing to hold permanent “forever” capital. If you can do these two things it seems to me you will probably do well. The bigger question is — how many people have the guts to do this for the long term? I suspect few — this is why asymmetric opportunities exist.

Note 1: Efficient Market Theory

The big argument of indexers is that the market is efficient and random — you can’t predict it or anticipate it, so you might as well own everything, because it is priced “perfectly”. Here is the stock chart of Wirecard AG, once the high-flying wunderkind of Europe:

Rational, huh?

Note 2: The erosion of shareholder rights with indexing

OK. Imagine if you are a giant index-fund like Vanguard or whatever. You own everything — and you own a large stake of it. You own x of Adidas and x of Nike. In theory you could put your votes to good use, and influence governance decisions, etc. But here is the thing: you own everything. You don’t care if Nike is doing better than Adidas — in effect you only care if the GDP of the world goes up, and people buy more shoes. That’s not going to ever lead to the best governance decisions for a company — by definition!

Note 3: Seth Klarman on the dangers of indexing

Indexing ……...becomes self-defeating when more and more investors adopt it. Although indexing is predicated on efficient markets, the higher the percentage of all investors who index, the more inefficient the markets become as fewer and fewer investors would be performing research and fundamental analysis. Indeed, at the extreme, if everyone practiced indexing, stock prices would never change relative to each other because no one would be left to move them.

Rakon

Corporate doublespeak press release from RAK this morning. Link. What I suspect is RAK wants the deal to go ahead and Skyworks is chiseling on price — expecting weak results given sustained weakness in telecommunications sector. Still cheap based on comps and fundamentals — at 94c it is trading on the lower end of sector peers. As with everything, caveat emptor…

Clearly Skyworks (alleged bidder) did their homework and came up with a valuation of $1.70 — this is well above Forbar’s valuation of 0.98c per share. Would be useful if RAK explained the bidder’s valuation methodology to market.

Many years ago my grandfather told me about Sir Julian Smith, the owner of the ODT — i.e. the country’s best newspaper — turning up in a battered Toyota wearing attire that had clearly seen better days. Moral of the story: be wary of those who drive sports cars!